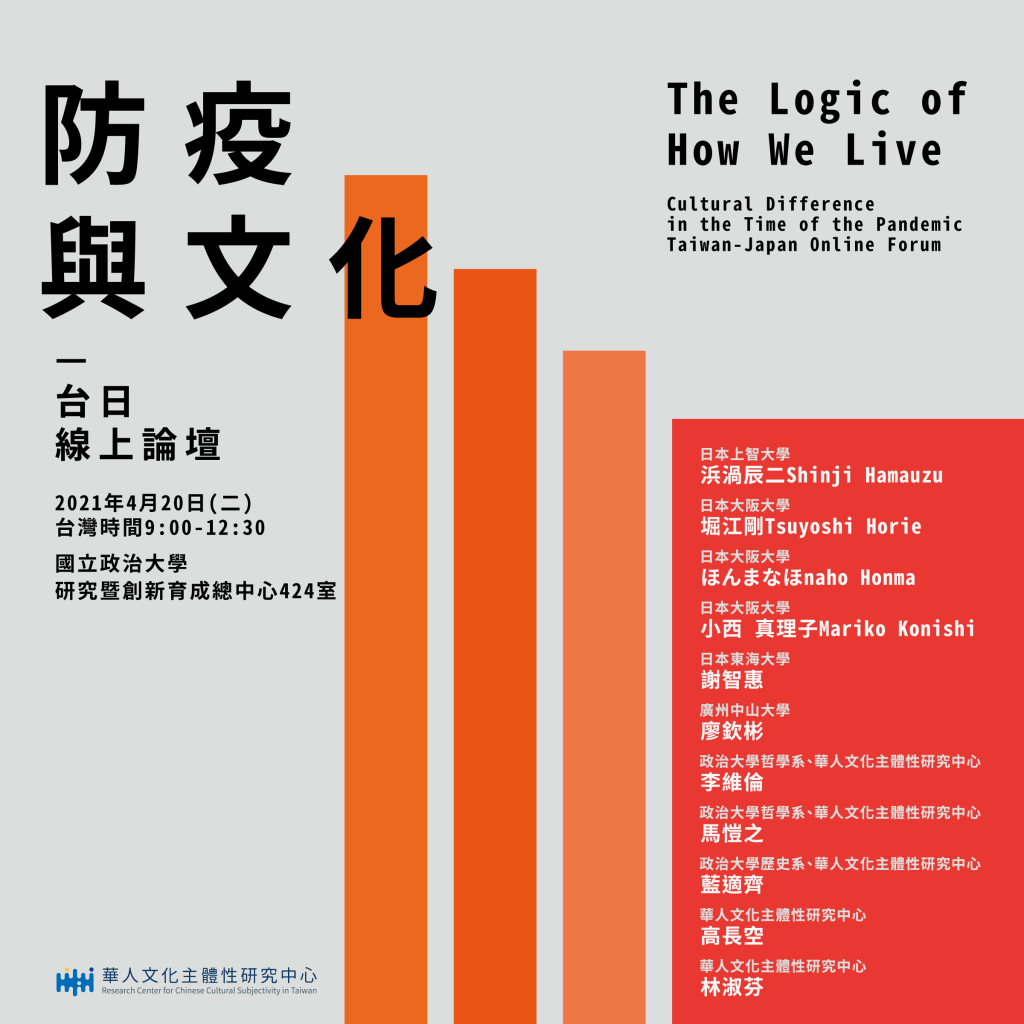

本中心華人倫理實踐研究群、華人思維模式研究群共同發起「防疫與文化—台日線上論壇」,邀集日本上智大學、大阪大學、東海大學等數位學者加入,於4月20日(二)早上9: 00(台灣時間)針對防疫與文化相關議題進行討論,論述防疫過程中的文化因素,並研議進一步合作研究的可能性。活動要旨與討論題綱如下:

長久以來我感到羞愧。儘管沒有直接參與,儘管是出於善意,也還是一樣,羞愧得想死,只因為自己也曾經是個殺人兇手。漸漸地我認識到,即便是高人一等的人,到了今天也難免要殺人或放任他人殺人,因為這是他們生活的邏輯。而在這個世上,我們的一舉一動都有可能置某人於死地。—卡繆.瘟疫

For a long time I have been ashamed, mortally ashamed, of having been — even at a distance, even with the best will in the world — a murderer in my turn. With time I have simply noticed that even those who are better than the rest cannot avoid killing or letting others be killed because it is in the logic of how they live and we cannot make a gesture in this world without taking the risk of bringing death.” (A. Camus, The Plague, part 4, translated by Robin Buss, first published by Allen Lane The Penguin Press 2001)

自今年(2020)初爆發新冠疫情以來,原有的世界與人類發展設想驟然失效,全世界陷入巨大的裂縫之中。病毒侵害人命誠然有其生物醫學的科學原理,但世界各國不同的致病率與致死率,卻是涉及了各個社會不同的文化價值與社會行為。「生活的邏輯」:即卡繆在小說《瘟疫》(The Plague)中指出的,社會中每一個人都贊同但卻導致人們喪命的行動與原則。這些原本作為人們生活行動的正面道德與價值指引,在疫病來襲時卻成為為死亡鋪路的陰影。雖然卡繆的警言很難以數據來證成,但每個受衝擊的社會不免需要對其於疫情中失效的生活邏輯加以反思,不僅是為了預防未來,更是為了認識其理所當然之價值的限制。

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic at the beginning of 2020, the available beliefs about the world and human development have been suddenly invalidated, and the whole world has fallen into the abyss. It is true that the way in which viruses damage human life has scientific and biomedical reasons, but the divergent infection and fatality rates of various countries in the world also reflect the different cultural values and social behaviors of different societies. With the idea of “The logic of how we live”, Camus pointed out in the novel The Plague (La peste) that everyone in a society agrees with the actions and principles that cause people to die. These are usually seen as positive moral and value frameworks that guide people’s life and actions, but when the epidemic strikes, they become the shadow that paves the way for death. Although Camus’ warnings are difficult to prove with data, every affected society inevitably needs to reflect on the “logic of life” that fails in the time of the epidemic, not only to prevent future disasters, but also to recognize the limitations of the values that the society takes for granted.

因此,面對至今未歇的新冠疫情,每一個國家社會都有必要進行對自身文化與社會價值行為進行反省。然而這項工作並非易事,因為其對象是各個國家社會理所當理的「生活邏輯」。因此一項可行的方法是透過不同國家社會之間誠懇與開放的相互對比,彼此協助,找出自己國家的社會行為在面臨疫情時的弱點,然後開放到各自社會中交由大眾討論,尋求適當的文化重塑,以形成新的防疫價值行為。

Therefore, in the face of the not yet controlled COVID-19 epidemic, it is necessary for every country and society to reflect on its own culture and social values. This work is not an easy task, because its object is the “logic of life” that every country and society considers reasonable. Therefore, a feasible method is to engage in a sincere and open work of comparison between different countries and societies, in order to help each other to find out the weaknesses of the social behavior of one’s own country in the face of the epidemic, and then to open up the discussion to the public of the different societies to seek the appropriate reshaping of one’s culture and to encourage new counter-epidemic values and behaviors.

臺灣政治大學華人文化主體性研究中心因此設想一項的臺日網上論壇,並邀請您加入我們一同思考彼此社會中的文化價值與社會行如何參與到防疫的政策與作為之中。

In order to discuss these questions, the Research Center for Chinese Cultural Subjectivity in Taiwan at the National Chengchi University wants to organize a Taiwan-Japan Online Forum. With this purpose, we would like to invite you to join us in thinking about how cultural values and social behaviors in each other’s society can contribute to the development of better epidemic prevention policies and actions.

- 討論題綱 Topics for discussion

疫病攻擊的是社群而非僅是個人。在這次COVID-19的防疫過程中,個人隱私和公共衛生之間出現了張力,各國政府和人民對此反應不同,似乎涉及了不同社群的文化因素與政府體制的問題。以台灣為例,台灣人對於數位治理對個人隱私侵入的疑慮較沒有敏感度,例如防疫初期,透過健保卡和手機定位等數位技術進行監控;而為了社群的安全,對日常行為受到節制較不反對,例如強力執行戴口罩,因此,我們想提出幾個觀察:

The disease attacks communities, not just individuals. During the COVID-19 counter-epidemic process, tensions have emerged between the right to personal privacy and public health concerns. Governments and people of various countries have reacted differently to this, reflecting the cultural and political factors that shape the response of different communities. Take Taiwan as an example: Taiwanese are less sensitive to the intrusion into personal privacy of digital governance and, for example, in the early stage of epidemic prevention, monitoring was carried out through digital technologies such as health insurance cards and mobile phone positioning, and for the safety of the community the restriction of daily behaviors does not encounter strong objection, for instance the enforcement of the use of masks. Therefore, we would like to make a few observations:

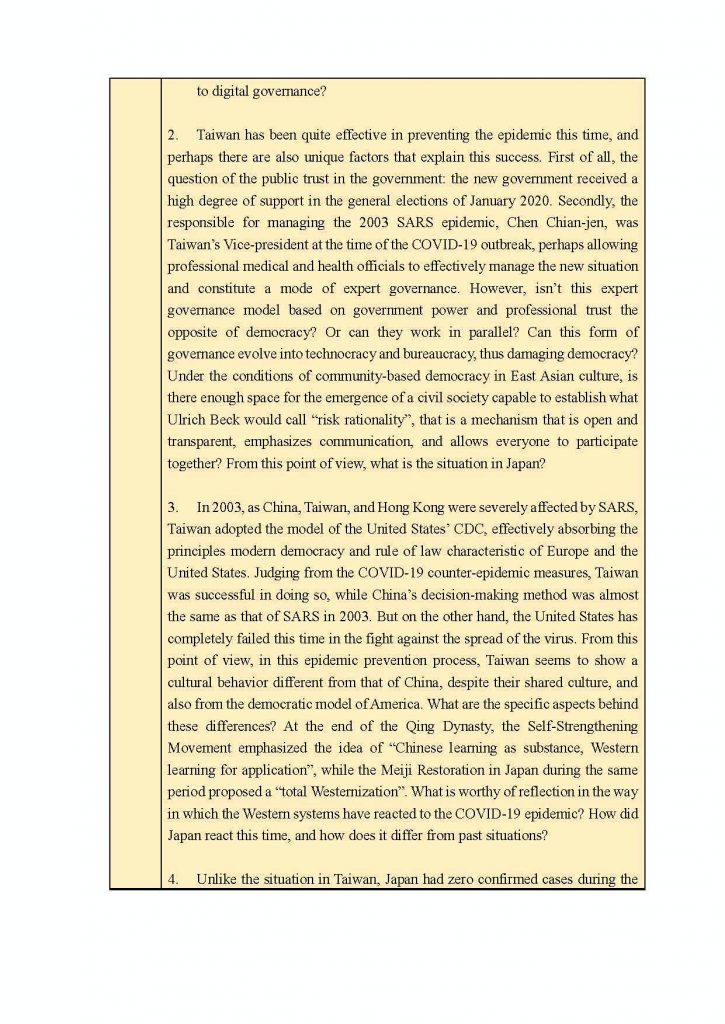

1. 數位治理在東亞的接受度較高,是否有著文化的因素?台日雙方國人對數位治理的反應如何?

The acceptance of digital governance in East Asia is relatively high. Are there cultural factors for that? How do the people of Taiwan and Japan react to digital governance?

2. 台灣這次在防疫成效上獲得相當不錯的成果,或許也有其獨特的因素。首先,2020年1月新政府得到的支持度較高,這涉及了對政府治理的信任(trust)問題。其次,2003年之後SARS的公共衛生體系建立人陳建仁正是疫情爆發時的副總統,或許也讓醫療衛生的專業官員可以有效地統理一切,形成專家治理的模式。然而,此一奠基於政府權力與專業信任的專家治理模式是否與民主形成反題?或者可以並行不悖?此一治理形式有無可能淪為專業加上官僚體制的後果,以致侵害到民主?在東亞文化的社群式民主的條件下,公民社會的能量是否可能建立貝克(Ulrich Beck)的風險理性概念:開放透明、重視溝通,允許大家一起參與的機制?就這一點來看,日本方面的情況如何?

Taiwan has been quite effective in preventing the epidemic this time, and perhaps there are also unique factors that explain this success. First of all, the question of the public trust in the government: the new government received a high degree of support in the general elections of January 2020. Secondly, the responsible for managing the 2003 SARS epidemic, Chen Chian-jen, was Taiwan’s Vice-president at the time of the COVID-19 outbreak, perhaps allowing professional medical and health officials to effectively manage the new situation and constitute a mode of expert governance. However, isn’t this expert governance model based on government power and professional trust the opposite of democracy? Or can they work in parallel? Can this form of governance evolve into technocracy and bureaucracy, thus damaging democracy? Under the conditions of community-based democracy in East Asian culture, is there enough space for the emergence of a civil society capable to establish what Ulrich Beck would call “risk rationality”, that is a mechanism that is open and transparent, emphasizes communication, and allows everyone to participate together? From this point of view, what is the situation in Japan?

3. 同樣作為SARS疫情嚴重的中國、台灣、香港,台灣學美國的CDC(疾病管制局),吸收歐美現代的民主、法治,由這次COVID-19的防疫過程來看,台灣是成功的,而中國的決策方式則幾乎是重蹈2003年SARS的覆轍。但在另一方面,美國卻是在抵禦疫情的傳播上全面淪陷。如此看來,台灣在這次防疫過程中,似乎表現出不同於中國華人文化行為以及美國社會的民主模式,其中是否有特殊之處?清末時自強運動強調「中學為體,西學為用」,而同時期日本的明治維新則是提出「全盤西化」,西方制度在這次疫情中顯像出甚麼值得反思之處?日本在這次疫情中,表現出與以往不同之處為何?

In 2003, as China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong were severely affected by SARS, Taiwan adopted the model of the United States’ CDC, effectively absorbing the principles modern democracy and rule of law characteristic of Europe and the United States. Judging from the COVID-19 counter-epidemic measures, Taiwan was successful in doing so, while China’s decision-making method was almost the same as that of SARS in 2003. But on the other hand, the United States has completely failed this time in the fight against the spread of the virus. From this point of view, in this epidemic prevention process, Taiwan seems to show a cultural behavior different from that of China, despite their shared culture, and also from the democratic model of America. What are the specific aspects behind these differences? At the end of the Qing Dynasty, the Self-Strengthening Movement emphasized the idea of “Chinese learning as substance, Western learning for application”, while the Meiji Restoration in Japan during the same period proposed a “total Westernization”. What is worthy of reflection in the way in which the Western systems have reacted to the COVID-19 epidemic? How did Japan react this time, and how does it differ from past situations?

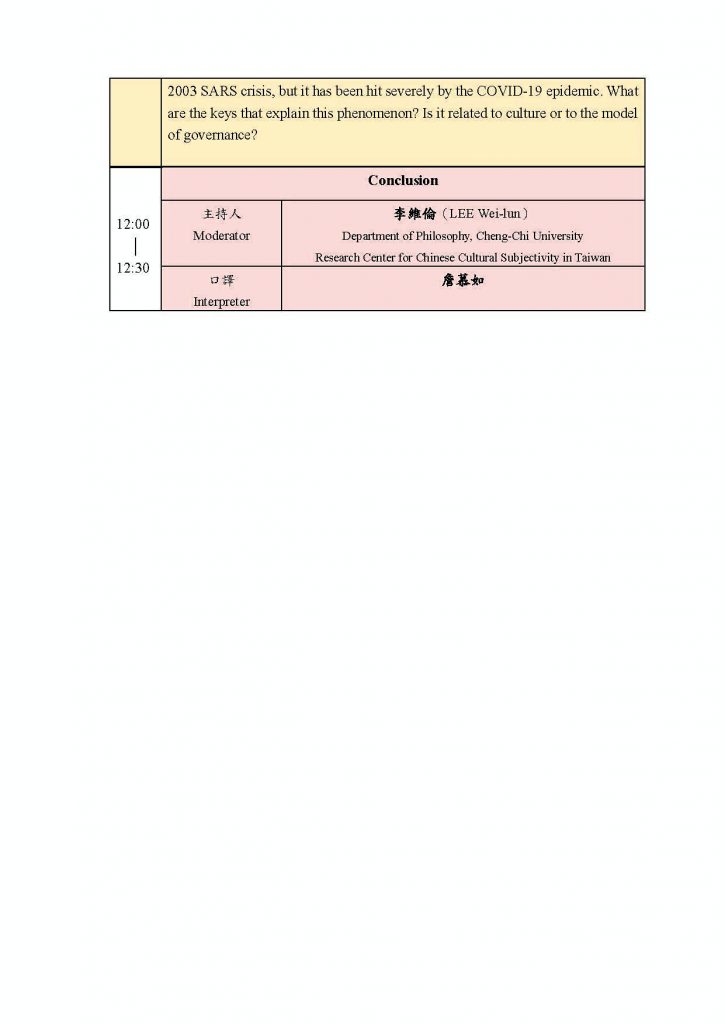

4. 與台灣的狀況不同,日本在SARS期間零確診,在此次COVID-19的疫情中卻成為重災區,其間關鍵為何?是否與文化或政府的治理模式有所關聯? Unlike the situation in Taiwan, Japan had zero confirmed cases during the 2003 SARS crisis, but it has been hit severely by the COVID-19 epidemic. What are the keys that explain this phenomenon? Is it related to culture or to the model of governance?

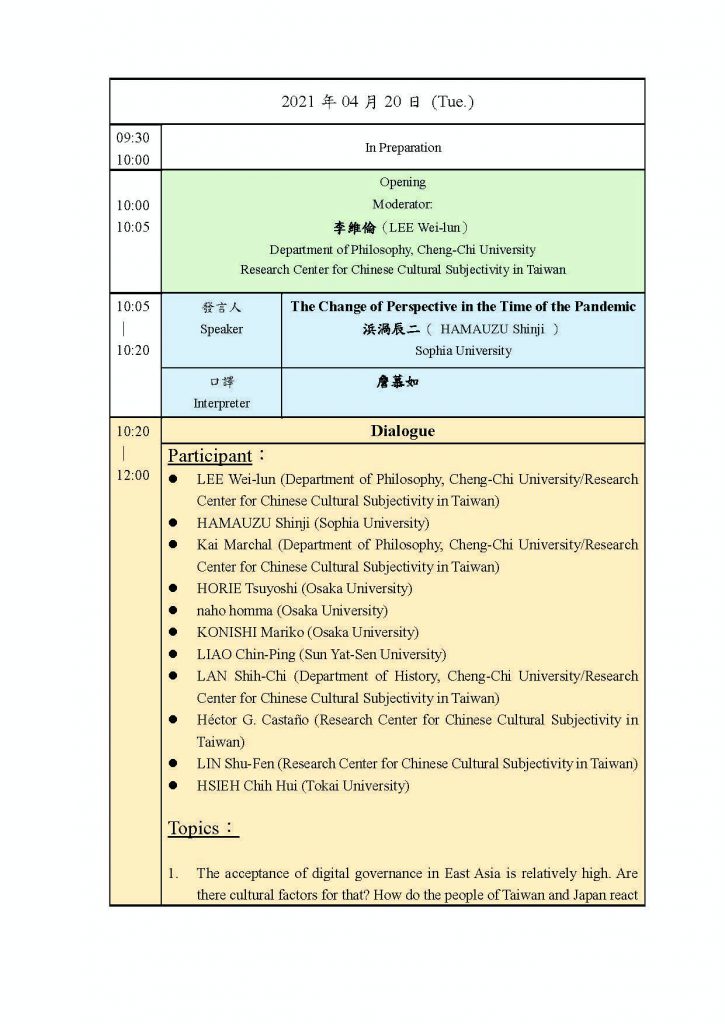

議程: